Last week marked the end of the negative interest rate era, when the Bank of Japan (BOJ) raised its policy rate by 0.10% (to a range of 0% to +0.10% from -0.10%). The world’s third-largest economy thus ended the experiment of negative interest rates put forth first by the European Central Bank (ECB) in 2014, followed by the Bank of Japan’s then-shocking announcement of negative policy rates in 2016.

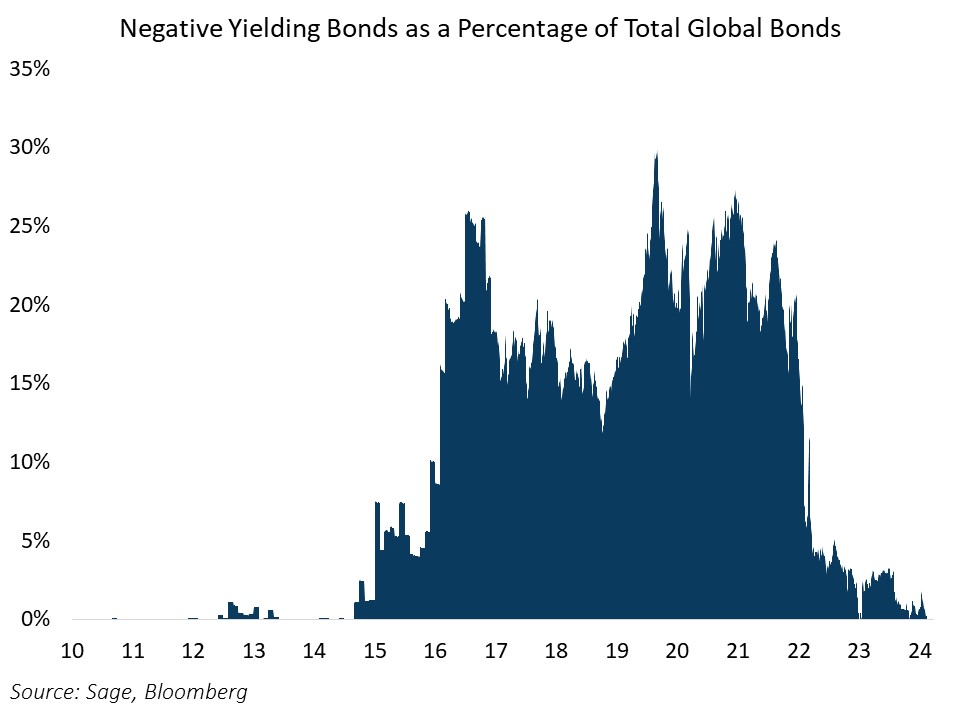

The prevailing narrative at the time assumed that if lower interest rates led to more borrowing, which would then stimulate the real economy, then a stagnant economy at zero interest rates simply meant rates weren’t low enough. Negative interest rate policy (NIRP) would charge depositors a fee, which should have resulted in capital leaving deposits and entering the asset markets or the real economy. In reality, borrowers never showed up as expected, and NIRP ended up backfiring, threatening European and Japanese bank profits. In fact, the policy was so ineffective that despite the economic malaise during the pandemic shutdowns, the US Federal Reserve ruled out the possibility of the federal funds rate moving into negative territory, and the BOJ and ECB chose not to dip deeper into negative territory. (At one point, negative-yielding bonds represented close to 30% of the global bond market.) Supply chain constraints coupled with gigantic government spending required global central banks to raise interest rates to combat inflation, which remains persistent today. The BOJ is the last central bank to escape NIRP.

Additionally, last week the BOJ scrapped its yield curve control policy and ended its ETF purchase program. As this policy shift was largely expected by markets, Japanese asset markets reacted positively, with equities rallying while the yen weakened against other major currencies.

Just as the BOJ finally joined in on hiking policy rates, it’s found that it’s the only major central bank at the party. In its March FOMC statement and press conference, the Fed continued to lay the groundwork for rate cuts this year.

As expected, there were no policy shifts from the FOMC during its March meeting last week. Versus the December FOMC release, the “dot plot” maintained its median of three rate cuts in 2024 while indicating one less cut in 2025 combined with a slightly higher long-term policy rate. Most notably, in its Summary of Economic Projections, the FOMC also raised its forecasts for GDP (from 1.4% to 2.1%) and inflation (core PCE from 2.4% to 2.6%), which was interpreted as accommodative by markets.

The Fed has indicated that it is willing to tolerate a stronger economy before changing its policy stance, as illustrated by the upgraded forecast for growth and inflation coupled with the same amount of rate cuts in 2024 as signaled at the December FOMC meeting. This increases the chance of rate cuts while raising the bar for a resumption of rate hikes, which is dovish.

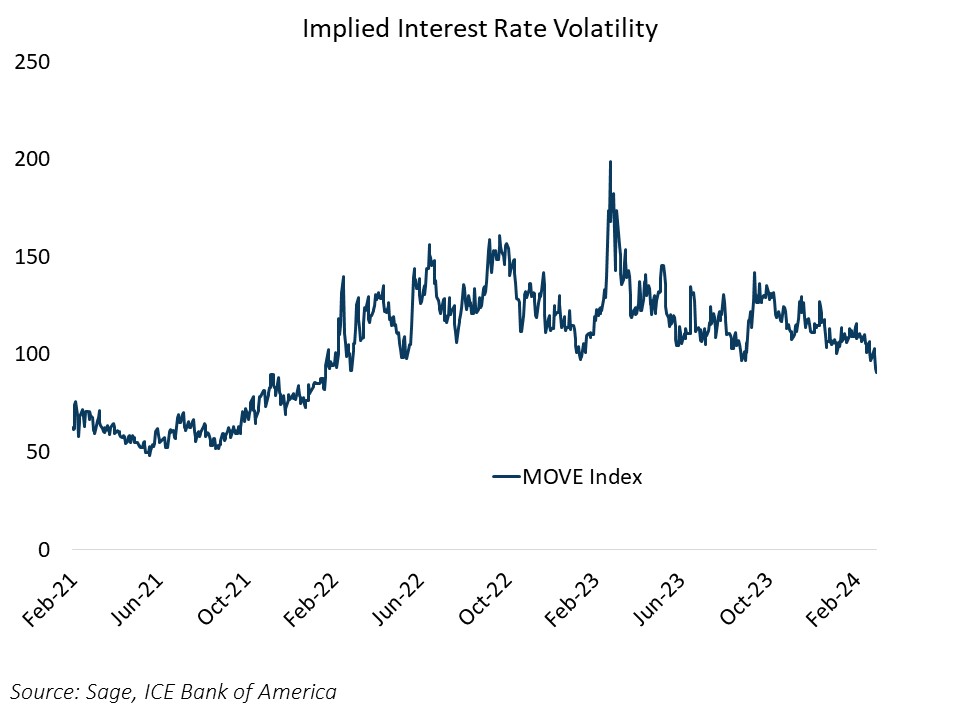

Markets responded in kind with corporate credit spreads grinding to the tightest level this year, despite record supply. Interest rate volatility, as represented by the MOVE Index, is now sitting at the lowest level since the onset of Fed rate hikes in March 2022 as markets continue to price in an easing cycle. This could present some interesting relative value opportunities.